Ethereum Block Proposal: A Technical and Shariah Perspective

By Sh Farrukh Habib, Chief Shariah Advisor @ InshAllah Network

By Sh Farrukh Habib, Chief Shariah Advisor @ InshAllah Network

This article, while citing the perspectives of wide range of scholars, generally approaches from a Hanafi perspective. In forthcoming papers, we’ll explore the same issue from other schools of thought.

The TL;DR

- Ethereum staking with validators is a permissible activity in essence, but the presence of haram transactions on the network raises some shariah concerns.

- If the income from haram transactions is not more than 50%, then staking is generally permissible with non-filtering validators. However, the income from haram transactions should be purified (given to charity).

- Haram transaction filtering solutions are ideal, like Goldsand. In the presence of such solutions, it is makruh tanzihi (disliked) to stake with non-filtering validators, even if condition #2 is fulfilled.

1. Introduction

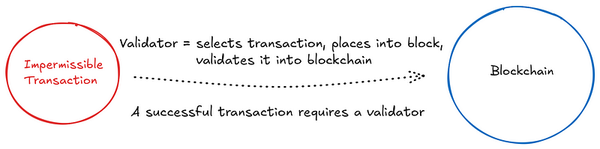

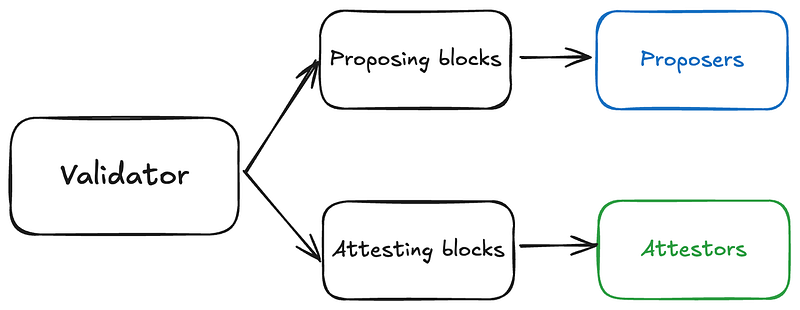

Ethereum’s transition to a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism introduced significant changes to how its blockchain operates, particularly in the roles of validators. A validator is a virtual entity that lives on Ethereum and participates in the consensus of the Ethereum protocol. Validators are responsible for ensuring the security and functionality of the network through two primary tasks: proposing blocks and attesting to blocks proposed by others. Proposing and attesting are together termed as ‘validation’, hence their role is named as ‘validators’.

However, for the sake of clarity and better understanding from the Shariah perspective, we will split these two primary tasks. We will also use different terms for each task and role based on their nature, such as:

- Validator — proposing blocks: ‘proposer’

- Validator — attesting blocks: ‘attestor’

In Ethereum’s PoS ecosystem, as mentioned before, validators play a dual role:

- Proposing Blocks: Proposers, randomly selected by the protocol, propose new blocks. This involves bundling pending transactions from the mempool and adding the block to the blockchain. Block proposers are rewarded with transaction fees and additional protocol incentives for their efforts.

- Attesting Blocks: Attestors participate in attestation of the proposed block. This process involves verifying that the proposed block meets the consensus rules of the network.

In this paper, we’ll look primarily at Ethereum block proposing and whether the income earned from it is halal. We’ll have future papers exploring Ethereum block attestation and other shariah issues around staking.

2. The Role of Proposers

A block proposer is tasked with creating a block by selecting pending transactions from the Ethereum ‘mempool’. This involves:

- Selecting Transactions: The proposer chooses which transactions to include in the block based on criteria like gas fees (priority fees) and block space. But notice that there is no obligation from the protocol to choose any specific type of transactions.

- Building the Block: Once transactions are selected, the proposer organizes them into a block that adheres to Ethereum’s consensus rules.*

- Submitting the Block: After assembling the block, the proposer submits it to the network, where other participants (attestors) verify its validity.

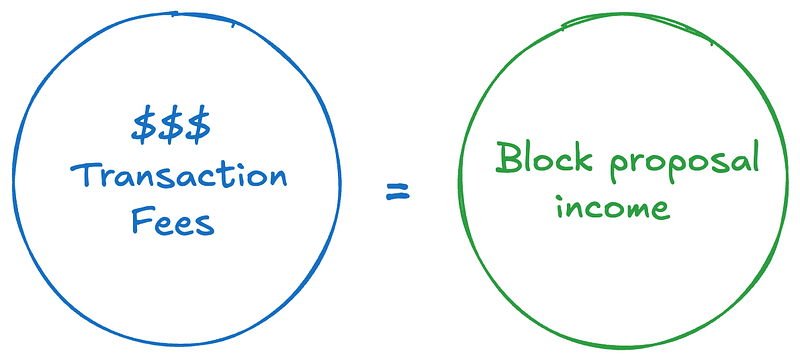

The rewards for proposing blocks include transaction fees (priority fees); fees paid by transacting parties for their transactions to be included in the block. This is the incentive for them to perform this task.

*Note: In practice, the proposer is often different from the builder, but for the simplicity of the analysis, we are not differentiating between the two.

2.1. Shariah Concern Regarding the Role of the Proposers

The major concern in the role of block proposers and their reward is whether this activity and its reward are halal or not, given that the transactions are mixed, halal and haram. The haram transactions although involve various types, they mainly come from the protocols that involve Riba transactions. The question is rooted in the Hadith of Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ).

حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الصَّبَّاحِ، وَزُهَيْرُ بْنُ حَرْبٍ، وَعُثْمَانُ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ، قَالُوا حَدَّثَنَا هُشَيْمٌ، أَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو الزُّبَيْرِ، عَنْ جَابِرٍ، قَالَ لَعَنَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم آكِلَ الرِّبَا وَمُوكِلَهُ وَكَاتِبَهُ وَشَاهِدَيْهِ وَقَالَ هُمْ سَوَاءٌ.

Jabir said that Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) cursed the accepter of interest and its payer, and one who records it, and the two witnesses, and he said: They are all equal. (Sahih Muslim 1598; https://sunnah.com/muslim:1598)

This hadith mentions different roles in a Riba-based transaction:

- Primary Parties: Direct participants in a transaction (e.g., lender and borrower in an interest-based loan). They initiate the transaction and negotiate the terms and conditions of the contract.

- Facilitators: These entities do not negotiate the terms or initiate the transaction, but they are directly involved in it as facilitators, such as the person who prepares the interest-contract (the writer of the document) and the witnesses to such a transaction.

While the roles of the primary parties, i.e., lender and borrower are clear, the roles of the scribe and witness of Riba is relevant in our context. The main concern is whether a proposer falls under the category of the facilitators, i.e., writer of the contract of Riba or witness of the transaction or not. To answer this question, we will examine what the hadith means by the terms, ‘the writer of the contract’ or ‘the witness of the transaction’. A famous Maliki Scholar of Hadith, Al Ubbi (died in 1424 CE) in his commentary on Sahih Muslim titled Ikmal Al Ikmal (إكمال الإكمال) explains this hadith by saying:

والمراد بالكاتب كاتب الوثيقة و بالشاهد المتحمل وإن لم يرد

What is meant by “the writer” is the one who writes the document, and by “the witness,” the one who actively witnesses it, even if they do not directly act in it. (2008, vol. 4, p. 279, Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah, Beirut, Lebanon)

This is further clarified when an accountant once asked Mufti Taqi Usmani, a world-renowned contemporary Hanafi scholar, about the permissibility of his work. The accountant’s job involved preparing financial statements, during which he had to record interest-related transactions as part of his client’s books. The accountant asked if his role fell within the scope of the curse mentioned in the Hadith. Mufti Taqi Usmani clarified:

It is true that according to a well-known Hadith, those who invoke the curse of Allah with regard to a transaction of Riba (interest or usury) include a person ‘who has written the interest’. However, this Hadith refers to the scribe of the transaction i.e. a person who has written an agreement or prepared the document to evidence the transaction. It does not include a person who was not involved in the transaction itself in any way, but while preparing the accounts of a person, has come across a reference to the Riba transaction and has recorded it as an event that has already happened without his involvement.

This is how the scholars have interpreted the Hadith: the classical Maliki scholar Al-Ubbi, the famous commentator of Sahih Muslim has explained the Hadith in the following manner: ‘By the word ‘writer of Riba’ the Hadith intends the scribe of the document evidencing the transaction of Riba, and by the word ‘witness’ it means a person who attended the occasion to become a formal witness in support of the transaction. The Holy Prophet (ﷺ) has held them all as equal in sin because the transaction took place only with their joint efforts.’

It is evident from these references that it is the writing of the document of Riba that invokes the curse of Allah and not its subsequent recording in a statement of the facts that already happened. Therefore, the case of an Accountant of a firm or a company is different from the person who is directly responsible for the operation of interests. (https://seekersguidance.org/answers/hanafi-fiqh/working-as-an-accountant-when-interest-transactions-are-involved/)

This view is also supported by the following scholars and institutions where they have given fatwas on the role of accountants who, knowingly but, incidentally must record interest-based transactions:

- Darul Uloom Deoband, India: https://www.darulifta-deoband.com/home/en/qa/64409,

- Shaykh Faraz Rabbani, Canada: https://islamqa.org/?p=36432,

- Sheikh Sohail Bengali (USA), Mufti Abrar Mirza (USA), & Mufti Ebrahim Desai (South Africa): https://askimam.org/public/question_detail/19110,

- Shaykh Abdul-Rahim Reasat, UK: https://seekersguidance.org/answers/hanafi-fiqh/does-noting-an-interest-based-transaction-make-an-accountants-job-impermissible/

2.2. Key Points from the Fatwas

From the Fatwas mentioned above, we understand that:

- If an accountant’s role involves recording interest-related transactions post-execution (e.g., noting them in balance sheets), it is generally permissible, because it does not fall in the category of writer or witness of Riba transaction. This is because they are documenting events that have already occurred and are not directly facilitating or initiating the transactions.

- Directly facilitating or initiating haram transactions (e.g., drafting interest agreements or calculating interest for loans) is explicitly haram.

- The former is seen as distant and indirect involvement, which is tolerated under Shariah principles of necessity and practicality (halal with conditions).

- While such roles are permissible under specific conditions, the fatwas often advise avoiding such work if feasible, emphasizing a preference (mandub) for roles entirely free of haram exposure, even when it is indirect and distant.

3. Islamic Legal Characterization (Takyif Fiqhi) of Block Proposal

To understand the responsibilities of block proposers in relation to Shariah, we must carefully examine their role within the context of classical Islamic jurisprudence. We should have a proper legal characterization (Takyif Fiqhi, تكييف فقهي) of block proposing activity and a block proposer’s role.

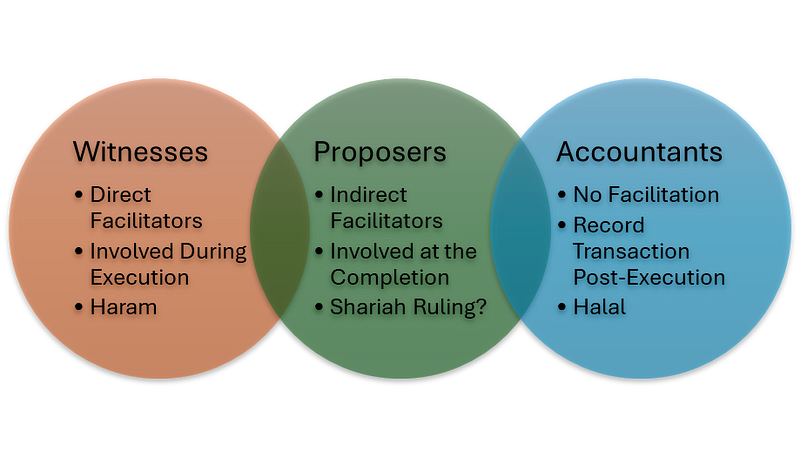

3.1. Proposers as Record Keepers

First, there are similarities between proposers and accountants. Proposers record and organize transactions on the Ethereum network. Their primary task is to select pending transactions from the Ethereum mempool, bundle them into blocks, and submit them for addition to the blockchain.

- Like accountants who record Riba transactions post-execution, proposers select and bundle transactions into blocks. They do not initiate or negotiate the terms of these transactions, making their involvement indirect and distant.

- Just as accountants do not decide the permissibility, or impermissibility, of transactions they record; proposers are not involved in the objective and purpose of transactions they include in blocks. Their role is procedural and necessary for the blockchain to function, akin to maintaining records in balance sheets.

However, there may be an argument that this analogy must be nuanced, as the role of proposers involves both documenting transactions and, more importantly, indirectly facilitating their completion. Unlike accountants, who typically record transactions post-execution (after completion), proposers have a role in the facilitation and finalization of transactions on the blockchain.

In the Ethereum context:

- If a proposer does not select a pending transaction from the mempool, that transaction remains incomplete and will not take place, as it is not added to the block.

- While proposers do not initiate or control the content of transactions, their selection of transactions with knowledge about haram transactions plays an indirect but essential role in ensuring their finality and completion.

This distinction highlights the proposers’ dual function as both recorders (post-execution, halal) and facilitators (during execution, doubtful), making their role partially unique compared to that of accountants. Hence, they are not exactly the same as accountants, but share some similarities with them. But does it mean that they are closer to the writer or witness of Riba? We will address this question in the next part.

3.2. Block Proposers as the Writer/Witness of the Contract

As mentioned above, the writer of the Riba transaction is the one who prepares the document or writes the contract. In our context, it is the creator/writer of the smart contract for the Riba-based transaction, because he/she is the one who codes the economic/business logic in the smart contract and codifies it. Once the smart contract is written, it automatically executes itself, hence intuitively, the smart contract itself will also become the writer or scribe of Riba transaction, because the terms are determined and execution of a Riba transaction is triggered by the smart contract. Subsequently, the smart contract effectively serves as the “writer” of the agreement, formalizing and enforcing the terms between the lender and borrower. This role, of the coder of smart contract and the smart contract itself, aligns closely with the role of the “scriber” mentioned in the hadith.

Proposers differ significantly from the “writer of Riba” mentioned in the Hadith. Proposers:

- Do not write smart contracts for such transactions.

- Do not negotiate the terms and conditions, content, purpose, and economic objective of any transaction.

- Do not initiate Riba transactions.

- Operate within a pre-set protocol that determines the rules for transaction inclusion, focusing on technical validity rather than purpose or intent of the contracting parties.

Therefore, proposers cannot be considered the writer of Riba contract, but it can be argued that a witness in a Riba transaction actively supports the completion of the deal by affirming and formalizing its terms in the presence of the involved parties. Although a witness is not involved in preparing the document, he/she does facilitate the transaction. As mentioned by Al Ubbi (Maliki scholar, died in 1424 CE) in his further text:

وفي معناها من حضر فاقره وانما سوى بينهم في اللعنة لأن العقد لم يتم إلا بالمجموع

Similarly, those who were present and approved the transaction are included. They are all equal in the curse because the transaction is not completed except through their collective involvement. (Ikmal Al Ikmal, 2008, vol. 4, p. 279, Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah, Beirut, Lebanon)

In the same manner, a proposer affirms transactions by selecting them for the proposed block. Hence, proposers in the Ethereum ecosystem may be akin to ‘witnesses’ of Riba-based transactions, as mentioned in the hadith.

To address this argument, first we should understand that a contract or transaction from the Fiqh perspective is completed when all the conditions (Shuroot) and pillars (Arkan) of a contract are found. The writer and witness of contract are neither required in the conditions nor in the pillars of a contract from the Fiqhi point of view (see Zuhayli’s Fiqh Al Islami Wa Adillatuh; and Mufti Taqi Usmani’s Fiqh Al Buyu’). Meaning that a transaction can be considered completed from the Fiqh perspective without a writer and witness of a transaction. The writer and witness are only mentioned in the hadith because they are facilitators and that is why they are included in the sin. Proposers may fall in the category of facilitators due to some similarity with witnesses, but it is clear that witnesses directly facilitate the Riba transactions, while proposers are involved indirectly.

Secondly, it is true that proposers play a supporting role in completing transactions by selecting them for inclusion in a block. This does lend some validity to the comparison with witnesses of Riba transactions, as both facilitate the completion of a transaction. However, the involvement of proposers is not equivalent to the direct and deliberate facilitation performed by a witness. While a witness actively formalizes and validates the terms of a transaction in the presence of the parties, proposers operate in a decentralized system where their primary role is technical and procedural, focused on maintaining the blockchain’s functionality. In this sense, they do have some similarity with witnesses, but at the same time, they are also different from the witnesses. Due to this fact, they are indirect facilitators, not direct ones like the witnesses.

3.3. Our Opinion on the Role of a Block Proposer

The above discussion highlights the proposers’ dual function as both partial recorders and indirect facilitators. It makes their role unique compared to that of accountants and the witness of Riba transactions. The role of a block proposer is partially like the accountants (halal) and partially to the witness (haram). However, this leads us to the question whether this nuance makes their activity and reward completely haram or halal? If it is halal, what are the Shariah basis for this decision and what are the conditions under which it is halal?

Based on the discussion, we consider that the whole activity of block proposing and its reward are not completely haram, our preferred view is that it is generally permissible but with strict conditions. The next section further clarifies the basis of this view.

4. Shariah Perspective on Proposing Blocks

The general permissibility of proposing blocks with strict conditions under Shariah hinges on several key principles derived from Islamic jurisprudence. In this section, we will discuss them and also discuss the conditions of permissibility.

4.1. Incidental Involvement and Tolerability

The proposer’s role in including transactions is indirect and incidental. The transactions are initiated by network users, not proposers. The proposers are only involved in the completion of transactions following the rules of the protocol at a later phase. They get involved in a transaction at a stage later than its inception. According to an Islamic legal maxim:

يُغتفر في البقاء ما لا يغتفر في الابتداء

What is excused in continuity [or at a later phase] is not excused at the inception [or beginning]. (Al Zuhayli, 2006, vol. 1, p. 424Al Qawaid Al Fiqhiyyah, Dar Al Fikr, Damascus)

Dr Muhammad Mustafa Al Zuhayli (died in 2016 CE), a famous Shafi scholar, mentioned this legal maxim in the category of the maxims that are agreed upon by all major four schools of Fiqh. He explains that it means that sometimes a thing can be established incidentally which cannot be established independently. A degree of leniency or tolerance in Shariah rulings is shown to something ongoing or at a later phase/stage than its initiation. He said:

In other words: What is not permissible at the inception may become permissible during continuity, or what cannot be established intentionally or independently may be allowed incidentally or as a subordinate. (Al Zuhayli, 2006, vol. 1, p. 424Al Qawaid Al Fiqhiyyah, Dar Al Fikr, Damascus)

While proposers may include impermissible transactions (e.g., Riba-based transactions) in the blocks they propose, this inclusion is an incidental outcome of maintaining the blockchain’s functionality. The act of proposing a block itself is a permissible and essential task for the blockchain’s operation. Therefore, proposers’ incidental involvement in facilitating haram transactions cannot render the whole activity as haram.

4.2. The Role of Intention

Proposers primarily act within a procedural framework, focusing on adherence to technical rules and network requirements rather than the intent of the contracting parties or nature of the transactions themselves. Proposers’ primary intent is aligned with a generally halal purpose: securing the blockchain and supporting its decentralized functionality.

In Islamic jurisprudence, intention (niyyah) plays a critical role in determining the permissibility of an act. Ibn Nujaim (died in 1563 CE), a renowned Hanafi scholar, in his book Al-Ashbaah wa Al-Nadhaair, states:

الْأُمُورُ بِمَقَاصِدِهَا

“Actions are judged by their intentions.” (Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiya, Beirut, 1999, p. 23)

To explain this legal maxim, an example can be given. A road maintenance crew tasked with ensuring roads are safe and functional. The crew’s primary purpose is to serve the public by maintaining infrastructure, which benefits everyone. However, they may know that some individuals will use these roads to transport haram goods or engage in impermissible activities, even if they are given statistics on how many people will use it for haram purposes. As long as they know that the haram activities are in minority, despite this knowledge, their role remains permissible because their intention and primary responsibility are focused on the road’s maintenance and utility, not on the activities facilitated by its use. Of course, this ruling will change if the majority of the activities carried out through this road are haram, because in this case, it will be considered that they are primarily facilitating the haram activities. But notice that it is a different basis, which may or may not change their intention.

Similarly, proposers in the Ethereum ecosystem, regardless of their knowledge of haram transactions, do not primarily intend to propose them when they build blocks. Their core objective is to maintain the blockchain’s security, ensure consensus, and ultimately receive rewards for this act, which is a permissible and beneficial activity. The inclusion of haram transactions in a block constitutes a small and lesser proportion of the total number and volume of transactions. Proposers do not act with an explicit intent to validate or support haram transactions, given the fact that Riba transactions are small in volume. They focus on the technical validity of the block; their work does not fall into general impermissibility.

4.3. Majority Rule and Practicality

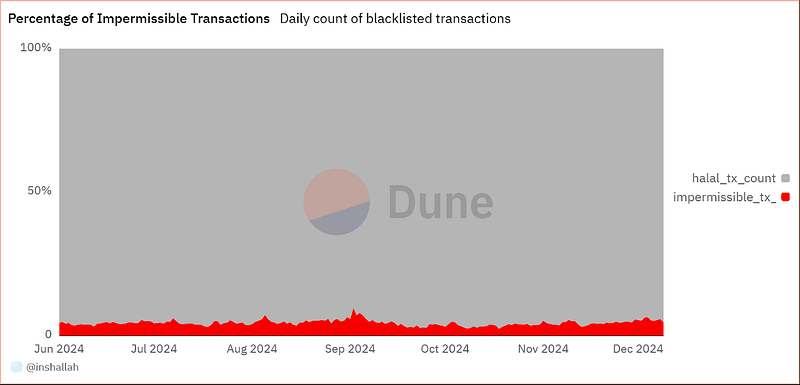

We have observed that haram transactions are not in the majority. Using DefiLlama, we analyzed the permissibility of all protocols that have Total Value Locked (TVL) above US$ 50 million. This represents about 97% of the TVL of all tracked applications on the Ethereum layer 1 (L1). According to our analysis, the average percentage of impermissible transactions is about 5% of the total number of transactions on Ethereum L1. The daily percentage of impermissible transactions ranges between 2.5% — 10%.

Analysis of the percentage of Impermissible transactions on the Ethereum L1

Since majority of the transactions are not haram, we can apply the Islamic legal maxim:

الْعِبْرَةُ لِلْغَالِبِ الشَّائِعِ لَا لِلنَّادِرِ

Consideration is given to what is predominant and widespread, not to what is rare. (Al Majallah Al Ahkam Al Adliyyah, Article: 42)

Dr Al Zuhayli, a famous Shafi scholar, explains this legal maxim as:

If a Shariah ruling is based on something that is predominant and widespread, it is applied generally to the whole. The occasional absence of that factor in some instances or at certain times does not affect the generality and consistency of the ruling. […] This is because, in Islamic jurisprudence, the foundational rule is to consider what is predominant. (Al Qawaid Al Fiqhiyyah, 2006, vol. 1, p. 325, Dar Al Fikr, Damascus)

Therefore, Riba transactions will not impact the whole activity of proposing blocks and its reward, making it completely haram.

4.4. Shariah Conditions for the Permissibility

Based on the Shariah principles outlined above, it is clear that proposing blocks is not completely haram, but does it mean that it is completely halal? The answer is it is halal but with some strict conditions. Notice that the strict conditions are important because without those conditions, this activity would become doubtful. And for doubtful things, a hadith is mentioned as:

حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ نُمَيْرٍ الْهَمْدَانِيُّ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبِي، حَدَّثَنَا زَكَرِيَّاءُ، عَنِ الشَّعْبِيِّ، عَنِ النُّعْمَانِ بْنِ بَشِيرٍ، قَالَ سَمِعْتُهُ يَقُولُ سَمِعْتُ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَقُولُ وَأَهْوَى النُّعْمَانُ بِإِصْبَعَيْهِ إِلَى أُذُنَيْهِ “ إِنَّ الْحَلاَلَ بَيِّنٌ وَإِنَّ الْحَرَامَ بَيِّنٌ وَبَيْنَهُمَا مُشْتَبِهَاتٌ لاَ يَعْلَمُهُنَّ كَثِيرٌ مِنَ النَّاسِ فَمَنِ اتَّقَى الشُّبُهَاتِ اسْتَبْرَأَ لِدِينِهِ وَعِرْضِهِ وَمَنْ وَقَعَ فِي الشُّبُهَاتِ وَقَعَ فِي الْحَرَامِ كَالرَّاعِي يَرْعَى حَوْلَ الْحِمَى يُوشِكُ أَنْ يَرْتَعَ فِيهِ أَلاَ وَإِنَّ لِكُلِّ مَلِكٍ حِمًى أَلاَ وَإِنَّ حِمَى اللَّهِ مَحَارِمُهُ أَلاَ وَإِنَّ فِي الْجَسَدِ مُضْغَةً إِذَا صَلَحَتْ صَلَحَ الْجَسَدُ كُلُّهُ وَإِذَا فَسَدَتْ فَسَدَ الْجَسَدُ كُلُّهُ أَلاَ وَهِيَ الْقَلْبُ ” .

Nu’man b. Bashir (Allah be pleased with him) reported: I heard Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) as having said this (and Nu’man) pointed towards his ears with his fingers): What is halal is evident and what is haram is evident, and in between them are the things doubtful which many people do not know. So he who guards against doubtful things keeps his religion and honour blameless, and he who indulges in doubtful things indulges in fact in haram things, just as a shepherd who pastures his animals round a preserve will soon pasture them in it. Beware, every king has a preserve, and the things God has declared haram are His preserves. Beware, in the body there is a piece of flesh; if it is sound, the whole body is sound and if it is corrupt the whole body is corrupt, and hearken it is the heart. (Sahih Muslim, 1599a, https://sunnah.com/muslim:1599a)

This hadith emphasizes the importance of avoiding doubtful matters to safeguard one’s religion and honor. In the context of block proposing, while the activity is not entirely haram, it involves incidental interaction with haram transactions, making it a potentially doubtful matter. By adhering to strict conditions block proposers can avoid falling into doubtful territory. Hence, proposing blocks is considered permissible under Shariah provided proposers take proactive measures to eliminate their exposure to haram transactions.

They must adhere to the following conditions to remain in the halal domain:

- Avoid Intentional Inclusion of Haram Transactions: Proposers must not deliberately select or prioritize haram transactions for inclusion in blocks.

- Ensure Haram Transactions Are a Minority: The number and volume of haram transactions included in a block must remain smaller than the halal ones. Proposers should actively monitor to ensure haram transactions do not exceed 50% in any block.

- Purify Income Proportionally: Proposers should purify a portion of their income equivalent to the proportion of haram transactions in the blocks they propose, addressing any incidental involvement in impermissible activities.

By fulfilling these conditions, proposers can ensure their work remains in the halal (Ja’iz) domain. Notice that the ideal approach is to have a solution that filters out haram transactions upfront and by using this solution, block proposers can select only halal ones. In this situation, no purification is required. This approach is recommended (mandub). While this approach may seem challenging, it is achievable through the Goldsand solution, which will be discussed later. Remember that in the presence of such a viable and better solution, the general activity of proposing blocks with the conditions will be considered disliked (makruh tanzihi), because in this situation, block proposers have a recommended (mandub) solution.

4.5. Shariah Compliance of Rewards of Proposers

Based on the previous discussion, we consider that the rewards earned by proposers are not completely haram, because transaction fees, while linked to the Riba transactions, are incidental and earned for the proposer’s technical service of ensuring the block’s validity, not for facilitating the nature or purpose of the transactions.

However, if proposers knowingly include impermissible transactions when they have the means to exclude them, this raises Shariah concerns. In such cases, proposers should purify their income by donating a portion to charity corresponding to the proportion of haram transactions they include, ensuring their earnings remain free from haram income. While, the reward from halal transactions is halal.

4.6. Purifying Income from Block Proposals

Proposers should calculate the proportion of haram transactions in their blocks and donate a corresponding percentage of their rewards to charity. Tools or mechanisms should be developed to determine this proportion, making purification a practical and manageable process.

The practice of income purification is rooted in the modern Islamic finance that ensures financial earnings remain halal (Ja’iz). Purifying income reinforces Prophetic guidance, as emphasized in the Hadith:

حَدَّثَنَا مُسَدَّدٌ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو مُعَاوِيَةَ، عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ، عَنْ أَبِي وَائِلٍ، عَنْ قَيْسِ بْنِ أَبِي غَرَزَةَ، قَالَ كُنَّا فِي عَهْدِ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم نُسَمَّى السَّمَاسِرَةَ فَمَرَّ بِنَا رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَسَمَّانَا بِاسْمٍ هُوَ أَحْسَنُ مِنْهُ فَقَالَ “ يَا مَعْشَرَ التُّجَّارِ إِنَّ الْبَيْعَ يَحْضُرُهُ اللَّغْوُ وَالْحَلِفُ فَشُوبُوهُ بِالصَّدَقَةِ ” .

Narrated Qays ibn Abu Gharazah:

In the time of the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) we used to be called brokers, but the Prophet (ﷺ) came upon us one day, and called us by a better name than that, saying: O company of merchants, unprofitable speech and swearing takes place in business dealings, so mix it with sadaqah (alms). (Sunan Abi Dawud, 3326, https://sunnah.com/abudawud:3326)

This hadith provides a valuable analogy for proposers in the Ethereum ecosystem regarding the purification of income. Just as merchants are advised to offset the inevitable lapses of vain talk (laghw) and excessive swearing in trade with acts of charity, proposers should address their incidental involvement with haram transactions through income purification. The Prophet’s guidance acknowledges that certain flaws are unavoidable in human activities, such as trade — and by extension, block proposals — but emphasizes the importance of taking proactive measures to rectify and cleanse these shortcomings. For proposers, while their primary intention and role are not completely haram and focused on maintaining the blockchain’s integrity, the inclusion of impermissible transactions requires income purification. By purifying a portion of their income corresponding to this involvement, proposers can ensure that their work and earnings align with Shariah principles, much like the merchants who mix trade with charity to cleanse their dealings.

5. Goldsand Solution

As we indicated earlier, the ideal solution (mandub) for proposers is to adopt filtering systems to exclude transactions from impermissible protocols upfront. In this way, block proposers can completely avoid proposing and facilitating haram transactions. Moreover, they will not need to purify their income.

It should also be noted that staking in general is considered halal (Ja’iz) under Shariah principles. However, this ruling becomes disliked (makruh tanzihi) in the presence of a completely halal solution, such as Goldsand, that actively avoids haram transactions. Choosing such an option not only fulfills Shariah obligations but also aligns with the principle of prioritizing the best available practices in the staking space.

To address this issue, Goldsand has been developed as a Shariah-compliant Ethereum staking solution. It filters out haram transactions from the mempool upfront, ensuring that proposers do not have impermissible transactions emerging from Riba-based protocols or other haram platforms. By integrating a transaction screening mechanism, Goldsand plays a vital role in aligning the proposer’s technical responsibilities with Shariah guidelines.

This approach allows proposers to fulfill their critical role in the Ethereum ecosystem while minimizing Shariah concerns. Goldsand’s filtering mechanism not only enhances the Shariah credibility of the proposer’s work but also provides a model for responsible blockchain participation, making their involvement in transaction facilitation both permissible (recommended) and aligned with Islamic values.

6. Conclusion

The activity of block proposing is not similar to the writer of Riba transactions, which is mentioned in the Hadith as haram. It is a unique activity in our context, distinct from both the role of the witness of Riba transactions (haram) and that of an accountant (halal). While it shares certain characteristics with these roles, it cannot be fully equated to either. Proposers do not create, negotiate, or enforce the terms of transactions; their role is procedural, involving the technical inclusion of transactions in a block. However, by completing transactions on the blockchain, proposers inadvertently facilitate haram transactions, such as Riba-based contracts.

This incidental involvement does not render the activity entirely haram, given the role of intention, the technical nature of the proposer’s task, and the typically small proportion of haram transactions within blocks. Consequently, block proposing can be considered halal (Ja’iz) but with strict conditions. These conditions are as follows:

- The proportion of haram transactions within each block must remain less than 50%, ensuring that halal transactions predominate.

- Proposers must purify their rewards in proportion to the haram transactions included in their blocks, addressing their incidental involvement.

While the above conditions render the activity permissible, the ideal and recommended (mandub) approach is for proposers to fully avoid haram transactions by implementing filtering mechanisms, or to use the solution offered by Goldsand. This system ensures the exclusion of impermissible transactions, allowing proposers to align their activities more closely with Shariah principles.

In the presence of a filtering system like Goldsand, the permissibility (Jawaz) of general block-proposing becomes disliked (makruh tanzihi). Proposers are strongly encouraged to adopt such solutions, making their work not only permissible but also ethically sound and aligned with the highest standards of Shariah compliance (Al Nadb). By taking proactive measures, proposers can fulfill their critical role in the blockchain ecosystem while upholding their Islamic obligations.